Index

Web Series: Model Boy a 6 episode indie Youtube dramatic tv series

Vogue: The Modeling World’s Sudanese Stars mini doc

Vogue: Inside the Life of Bella Thorne mini doc

NYT: The Stars of Cannes actor portfolio shot by Peter Lindbergh

NYT: Ballad of a Thin Man iconic rocker portfolio shot by Mikael Janssen

NYT: Expatriate Games thrilling political/social exposé

NYT: Friday Night Fights scoop on an underground male model fight club

NYT: Julian Assange getting a portrait of the international takes a bit of spycraft

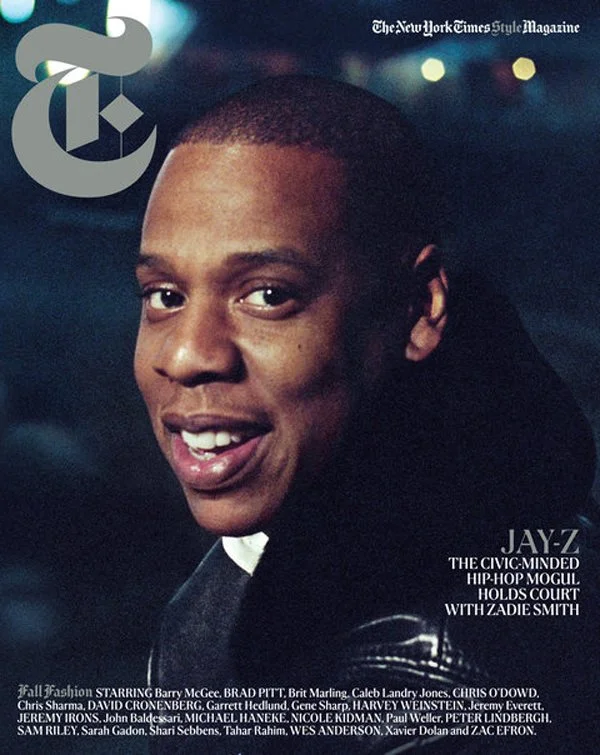

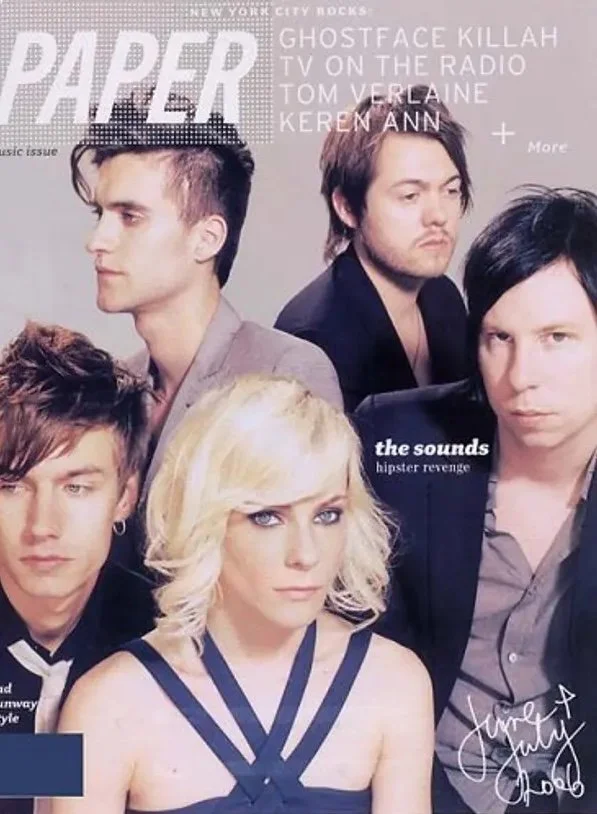

A few favorite magazine cover shoots

Model Boy

A gritty drama exploring the lives of these wide-eyed young guys lured into New York’s notoriously fickle high fashion modeling world. Sexually objectified, subject to the male gaze, paid in little more than social prestige—which of these ‘male ingenues’ will parlay a moment of fleeting fame to achieve his dreams, and which will the industry chew up and spit out?

Vogue: The Modeling World’s Sudanese Stars Share Their Stories

Angok Mayen and George Okeny have overcome countless challenges to achieve their goals and work for the greater good.

Vogue: Inside the Life of Bella Thorne

After a hyper image-managed childhood as a Disney star, Bella Thorne is offers her millions of fans an unfiltered picture of herself as she strikes out into new professional territory and seizing the reins of her life for the very first time.

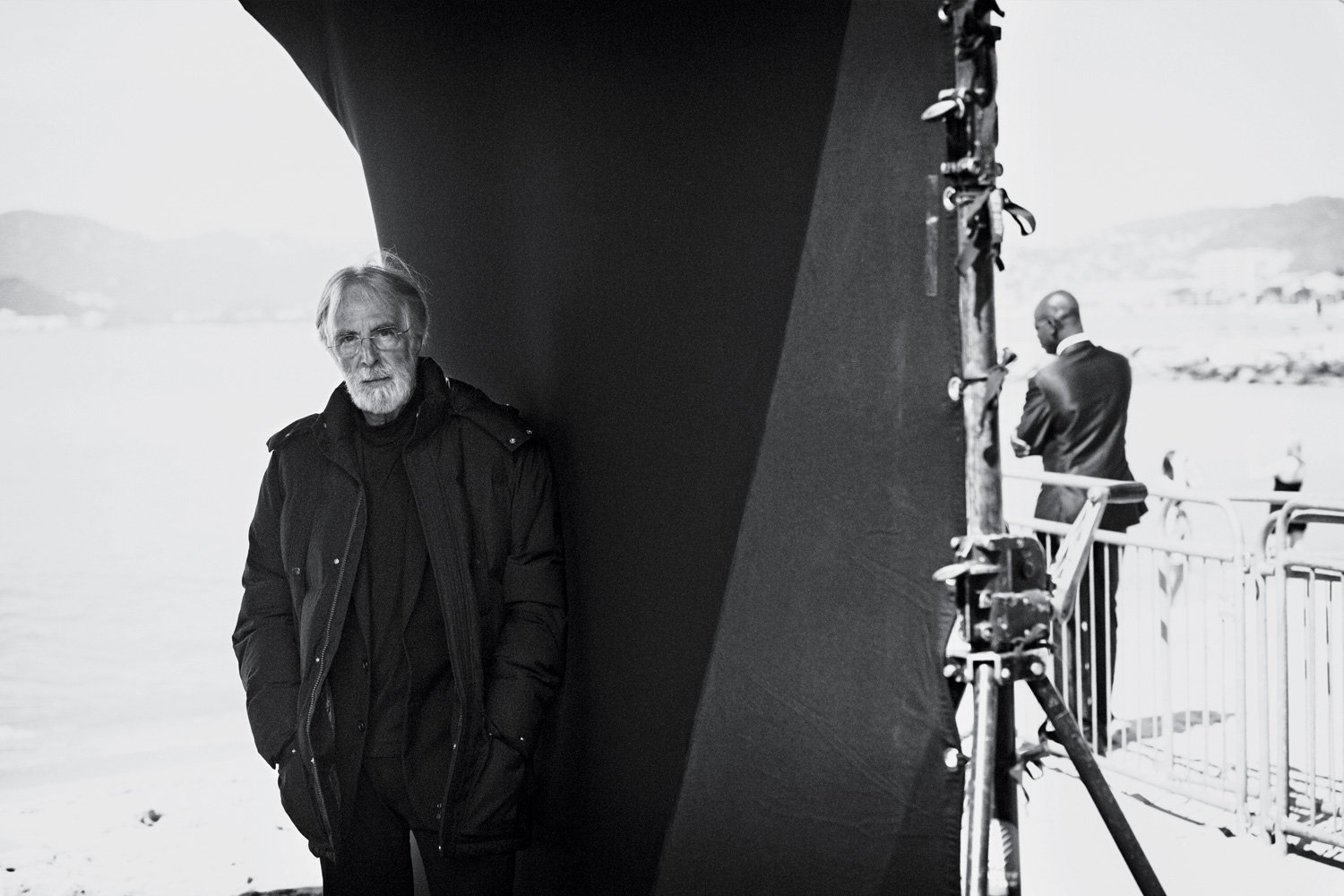

The New York Times:

The Stars of Cannes

Hollywood glamour on the Plage du Midi.

Photographed by Peter Lindbergh

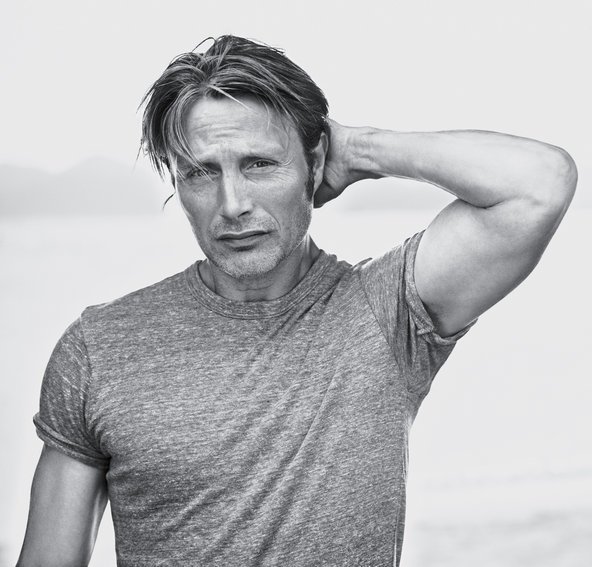

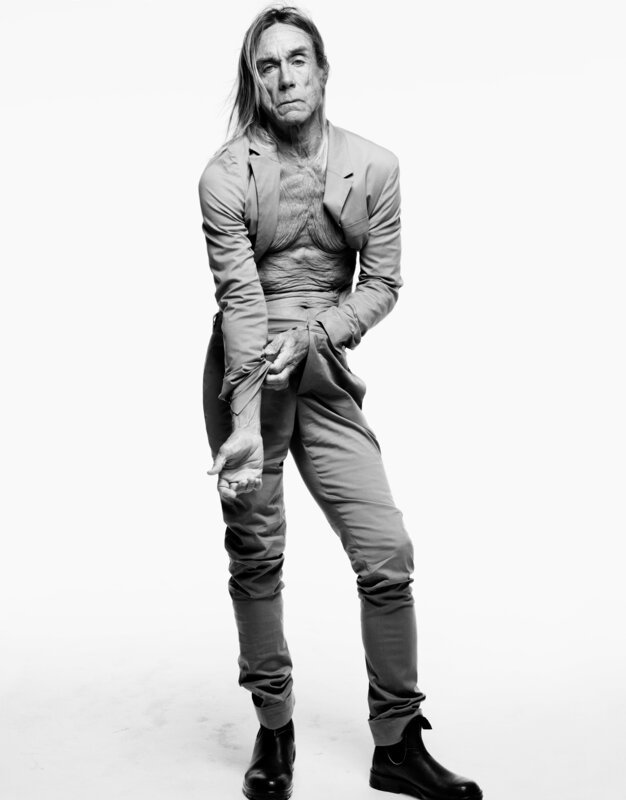

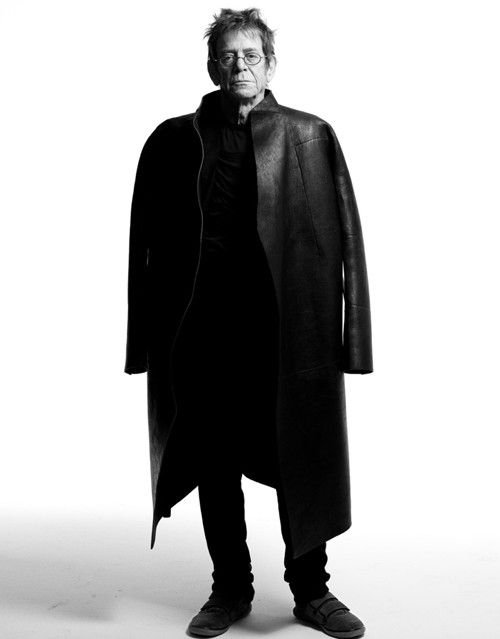

NYT Style Magazine:

Ballad of a Thin Man

The season’s iconic suits on a generation’s iconic rockers.

Photographed by Mikael Jansson

NYT Style Magazine:

Expatriate Games

For seven years, Josh Winters partied wıth the Mideast elite and lived to tell about it.

-

"This is the story of a person who does not claim to be a fighter for patriotic causes, a political leader or diplomat, it is merely a story of an ordinary citizen, who found himself thrust into the midst of events he had no choice but to be a part of — events he could neither evade or distance himself from, as they unfolded. This is just a story of a Yemeni citizen.”— Mohsin Alaini from his book, “ 50 Years in Shifting Sands,” translated by Hassan al-Haifi

In 2003, I landed in Yemen for the first time to surf and study Arabic dialects. I traveled at the invitation of Haitham Alaini, a young entrepreneur who was educated at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. He had returned to Yemen to start a construction business that would eventually expand into oil and gas infrastructure, as well as security and I.T. He had a convoy of black Land Cruisers meet me on the tarmac and take me to his family’s home. The ride through downtown Sana’s trash-strewn streets was my first glimpse of a society seriously out of whack. During the next seven years, as I partied with the region’s high rollers and influence peddlers, the gulf between privilege and poverty would only get wider and more surreal.

Alaini’s family home is in the city’s diplomatic quarters. Its walls are hung with pictures of Haitham’s father, Mohsin, posing with J.F.K., with Zhou Enlai, with Nasser and with several other luminaries of the Arab Nationalist Movement of the ’60s and early ’70s. Mohsin Alaini was Yemen’s prime minister five times during that tumultuous period. His son, my host, grew up shuttling between world capitals, as Yemen split and reunited, north and south swept up in the two ideological passions — Arab nationalism and Soviet-style socialism — of the 1960s. By the early ’80s, whatever was left of the Arab Al-Nahda (renaissance) was replaced by a culture of lavish consumerism fueled by oil wealth.

Mohsin Alaini now lives and writes in Cairo, the city where he attended law school in the 1950s. Although most of his writing is political, he published a memoir that’s a snapshot of an Arab world rocked by dissent, much as it is now. He was part of a small group of Yemeni intellectuals who, inspired by the Egyptian revolution of July 1952, returned to Yemen intent on modernizing the country and establishing a republic. This is the ironic heritage of those autocratic regimes that have been upended by popular protests this year.

Alaini generously provided my friends and me with a Land Cruiser, two bodyguards, a satellite phone and a stack of guns. The next morning we left mountainous Sana by road, bound for the provinces. We didn’t return for 12 weeks as we explored every cove and peninsula of Yemen’s rocky Indian Ocean coast. This began my long and happy relationship with the rougher parts of Yemen and the Horn of Africa.

The desert coast of Somalia is another matter. Getting there is difficult. Somalia has little in the way of infrastructure, never mind consistent flight schedules available online. When my friends and I decided to surf there, our first stop en route was Dubai, where several Somali political exiles corralled us into endless meetings over Turkish coffee pleading for us to reinstate them to power. We nodded sympathetically and told them we had no means to help them. They smiled conspiratorially. It seems an American abroad is always thought of as a C.I.A. operative, unless he’s on safari or sketching a French cathedral.

When we eventually made it to Galkacyo, the main city of Somalia’s northern state of Puntland, we were collected from the airstrip by yet another convoy of Land Cruisers bearing smiling men with guns. We would spend the next month driving up and down the coast of Puntland, from Ras Xaafuun down to Eyl, with its angry pirates and bleak sand dunes. Our host was a local businessman who maintained his own private militia, as one does in failed states. Abdirizak Osman was a soft-spoken warlord, a graduate of Brown, with a fondness for golf and summer vacations in the Hamptons. He kept his wife and children at a lavish home in Dubai but spent most of his time nurturing his telecom business: STC Puntland. His business was thriving at that time, partly because his main rival had its assets frozen by the United States after 2001.

Osman ran the business from a sparsely furnished compound where he could take shelter from family members and townspeople who collected outside the gates of his main home, demanding adjudication or electricity, or any of the thousand things that one takes for granted in a state that has a functioning government. Upon leaving, we took tea with him, thanking him for his hospitality and wondering what we could send him from the United States. He chuckled quietly and looked around his house, furnished like an Ethan Allen showroom. He said: “Six months ago, I ordered a container of cigarettes from an Israeli-American. I paid in advance $100,000, and he disappeared with my money. Perhaps you can look into that for me? And secondly, the road between Galkacyo and Garowe is in bad shape. I need it to be paved.”

As guests of a man who keeps a private army of several hundred, it’s tough to say no. We said we would do our best.

I shuttled back and forth to the Mideast until 2008, when I moved to Dubai to start a consulting business, leveraging my experience building overpriced spec homes for gaudy Russians back in Los Angeles. I rented a small one-bedroom apartment for a blistering $6,000 a month because it was the only available flat I could find. Compensation for white-collar expats who worked in Dubai was grossly out of proportion to salaries back home. The streets were dense with Italian luxury two-seaters and blacked-out Range Rovers. The city’s financial firms, eager to lure the investment capital of wealthy and reportedly impulsive Gulf Arabs, competed to have the hottest looking staff. Five-inch stilettos and pencil skirts were de rigueur office attire, and the red lacquered Louboutin sole was ubiquitous. One developer topped the competition by employing sensationally beautiful Romanian twins with bleached blond pixie cuts as his receptionists.

Every night promised a new soiree for some vanity project, from a gallery for abstract Iranian sculpture to an online shopping service where one could order books, iPods, cigarettes, all guaranteed to be delivered in less than an hour.

Kate was one of those luxury-loving expats: a 23-year-old Republican with an insatiable appetite for Missoni. She was the the brand manager for Veuve Clicquot, and she was running two or three parties every night. Every new boutique and new ayurvedic cosmetic line demanded a lavish bash with premium bubbly. The news of the American financial crisis was shrugged off. The Islamic prohibition on alcohol was shrugged off. This was Dubai, after all.

But by early 2009, things started to change, and no one wanted to talk about it. The opportunistic expats quietly bolted, even though Dubai’s oldest families thought it best to proceed as if nothing had changed. Conspicuous consumption began to slacken, and major construction projects went silent. The mass exodus of white-collar workers sent rents plummeting. The long-term parking lot of the airport was full of abandoned Ferraris and Range Rovers, left by fired expats who had no intention of trying out Dubai’s breach-of-contract laws. Bankruptcy laws were still a year away, and debtors’ prison was the rule.

Luckily, that summer, I was awarded a big project in the Yemeni capital. The coastal drive from Dubai to Aden is fantastic at any time of the year, but the summer monsoon is the best. The difference between Yemen and the other states on the peninsula is stark: Yemen has a large and impoverished population, larger than Syria and almost as populous as Iraq. Just across the peninsula in the Gulf States, per capita incomes are in the $40,000 range, while in Yemen it is closer to $1,000. The disparity and proximity make the restlessness in Yemen understandable. The first time I crossed the peninsula, it was on a barely discernible track. This time, it was on a freshly paved highway where armed trucks from police checkpoints pulled in behind me as escorts for each stage of the road.

I rented a single-story house made of stone quarried from the surrounding mountains, in the leafiest part of Sana’s diplomatic quarter. I used the main hall to adapt local 150cc bikes into little cafe racers. The landlady was a Yemeni whose age was impossible to discern behind her hijab. Her English, though, had a flat Midwestern cadence. She arrived once a month to collect the rent and to complain about the foliage in the courtyard. The occupant before me was the Dutch embassy, and they had very nice furniture, she told me. I asked why the garden was such an untamed wilderness when I arrived. She addressed me by my full name, and said that the issue was not Dutch gardening, but her disappointment in me as a tenant; as an American, she expected more.

My new assignment brought me back into contact with Haitham Alaini, who had in the interim years befriended a couple of Afghan businessmen who ran their businesses from the comfort of Dubai. Kabir Arghandiwal, his neighbor in a high-rise called the Capricon Tower, was an affable fellow who loved Ed Hardy shirts and Diesel shoes. His Lebanese wife was a social fixture on Dubai’s art scene who reputedly made Kabir promise in a prenup that he could never take her nor their children to Afghanistan. He and his extended family manage logistics contracts for the ISAF forces in Afghanistan, and he is a partner in a passenger air service, FlyDubai.

Saad Mohseni was the third member of this group of Dubai neighbors who were sometimes called “the axis of evil” by their American friends. As chairman of the Moby Group, which he founded, Saad Mohseni was Afghanistan’s first media mogul. Not only has he pushed programming that provokes religious conservatives and government officials alike, but he has also built his media empire on ad revenue, which is astonishing in a war-ravaged economy. From his first days as a USAID-funded upstart until today, when ex-State Department staff work to expand his media efforts across the globe, he has shown a keen sense of how to balance politics and profitability. A headline in a local paper recently called him “Top Adman,” which is less glamorous than “the Rupert Murdoch of Afghanistan,” but perhaps more accurate. His success has opened many doors, including a partnership with the real Murdoch for an Iranian TV network based in Dubai.

On a warm quiet Friday morning in 2008, I joined Mohseni and Alaini outside a Starbucks in the financial center. Mohseni was wearing the weekend uniform of Dubai’s ascending power broker: cotton walking shorts belted a bit high, sockless loafers and an expression of haughty indifference. His wife, Sarah Takesh, was dressed in cotton hippie-chic of her own design, made by her company in Kabul. She was reading “The Dirt,” the Mötley Crüe story. Saad made polite conversation; Sarah made a point of being engrossed in the history of rock. They bickered over the details of their coming vacation in the Maldives. They fussed about shipping damage to their custom-made furniture, in transit from workshops in Kabul.

Mohseni and Alaini had been brought together by an interesting and universally admired character in Middle Eastern politics: Tom Freston, who has been tireless in his efforts to connect Mohseni to media players and politicians in the United States. He brokered Mohseni’s partnership with Murdoch, and has been in many ways his mentor. It may seem curious that the man who was head of Viacom should be trolling war zones for protégés, but Freston is a man of many interests. While balancing his involvement in Oprah’s new network with Bono collaborations, he maintains an unusual itinerary. In 2009, before Yemen topped America’s National Security priority list, he came to Dubai, to discuss a TV station in Yemen with Mohseni, among other things.

As of last year the TV station was still a work in progress. Mohseni met me for brunch at Baker & Spice in Dubai. While Sarah chatted about spending the rest of her pregnancy in the south of France, I asked Saad how long it would take for a TV venture like his to be profitable. He said one year. Clearly, he wasn’t counting on hustling airtime to local businesses at the going rate in Yemen (about $5 a second).

Later that summer, I traveled to Kinshasa, the capital of Congo, which by most estimates is among the poorest countries in the world, despite vast natural resources. I was a guest at the home of Rudy Ilumbe, a 26-year-old entrepreneur who grew up in Helsinki. Ilumbe is a big man who speaks quietly and listens intently. His English is smooth and polished, but he is more comfortable in French. His house is a sprawling Palm Springs-style ranch filled with Vitra furniture and an empty swimming pool. When I asked if he ever has pool parties, he said simply, “Swimming is for white people,” and then laughed. Other than the stock white Land Cruisers that his security detail rolls in, there was a Range Rover, a Bentley and an Audi S5 in the carport, each slammed and rimmed to match one another. We took the S5 out onto Kinshasa’s rutted dirt streets to the place where Ilumbe had recently booked 50 Cent. Over the first of many bottles of Perrier that his entourage racked up, Ilumbe toasted me and said: “I was always taught that nothing comes without hard work. In Finland I believed it and I worked hard, but I have to tell you; in Congo, making money is too easy.”

Ilumbe is tight with the president of Congo. He has secured gold, diamond and petroleum concessions for his European clients, and his consulting firm is booming.

Later that evening, Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso stepped up to the table, hat low over his eyes, swigging from his own bottle of Perrier. As is customary from Kinshasa to Beirut to Mumbai, each magnum of Champagne is brought to the table with lit sparklers and a shout-out from the D.J. The name of Sassou became irritatingly repetitive as the night wore on and the bottles stacked up. Denis Christel is the son of the dictator of Congo-Brazzaville, Congo’s neighbor. He has been accused of spending hundreds of thousands of dollars of the country’s oil revenues for shopping sprees in Paris, Dubai and Hong Kong. I excused myself from the table and moved through the packed club toward the restroom. Suddenly three guys materialized out of the crowd, escorting me through, and clearing the bathroom before I entered.

Somewhere toward the end of 2010, this story comes to an end with a bang, not a whimper. The day the cartridge bombs were discovered on planes in England and Dubai, I made some ill-timed inquiries to the offices of FedEx Yemen. The Yemeni military sealed the office, and because of my questions, I was told that I was no longer welcome in their country. Which is how I found myself exiled to East L.A. in late December, while across town at Soho House, Tom Freston convened a meeting with the owner of Yemen FedEx and other Mideast elite for a weeklong strategy session.

NYT Style Magazine:

Friday Night Fights

A series of underground fights in Manhattan lures a good-looking crowd, including the night's charismatic big draw.

-

The message rang out on Facebook early on Jan. 28. Those in the know immediately understood its meaning. One of the few public tip-offs that the underground fights would take place that night, it was quickly deleted by the downtown “It” girl who had posted it, likely at the behest of Friday Night Throwdown’s shadowy promoters. This would be their seventh such night, and they had learned not to take any chances.

Friday Night Throwdown always takes place in a Manhattan warehouse space — this time, in one of the weird buildings under the Manhattan Bridge, in Chinatown. A regulation ring is built, elevated and roped off. A serious referee officiates. There’s an announcer. A bell. Admission is charged. Cheap beer is sold. And there is a ridiculously good-looking crowd. The promoters are obviously well connected. Models pack the ringside — serious big-name girls and their male counterparts. Through the models, photographers like Steven Klein find their way to the site. Indeed most of the audience has heard about the fights on a fashion shoot, or from a model friend.

It is all so model-centric that people call it “model boxing” or even “the model fight club.” But despite the “Zoolander” jokes, the fighting is very real. Competitors are serious: they have experience in everything from Golden Gloves to muay Thai, with the occasional legit street brawler in the mix. Once in a while, an effete runway boy boxes as a novelty. Some of the more serious competitors “model on the side,” but they’re fighters first.

The organizers make a point to say these are not fight clubs, model or otherwise, explaining that “’fight club’ implies bare-knuckled brawling until someone is dead. That is clearly not what we do.” According to one frequent competitor who sometimes goes by the name Rockstar Charlie, “It’s careful. The ref is calling things sooner than you would find in a regular bout. He actually trains at the same gym I do.”

Rockstar Charlie has, since he made his debut on the second Friday Night Throwdown, been the event’s big draw, driving the occasion from small happenings among friends to something that is suddenly bubbling into the mainstream. He recruits other competitors. And his charisma and style in the ring drive the nights’ energy. He is quick to point out that headlining for him does not mean fighting last. He likes to party after inevitably defeating his opponent, and hence schedules his own fights on the early side, so he can join the crowd and cheer and drink.

At 6-foot-3, with a chiseled face and some amazing tattoo work, the 20-year-old is as unique a New York character as they come. He’s a pretty boy boxer. His day job is working with 2-year-olds in a nursery school. He rolls with a tight-knit crew called the Big Gunz that has been together since freshman year of high school — all good looking, all boxers.

Lately, partly thanks to the friends he’s made at the Throwdowns, he has been getting into modeling and may sign with an agency. Asked about the obvious tension between boxing and making money off your face, Charlie doesn’t engage. “I like a good lifestyle,’’ he says, “and teaching nursery school and boxing don’t pay well.”

That may change. Outside of the occasional underground matches, he’s got a few coming national tournaments that could lead to the super middleweight title. He’s undefeated in his weight, and a title would propel him toward the Olympics and then a pro career.

His trainer Leon Taylor is his biggest supporter. As he puts it, “There isn’t nobody gonna beat him.” Coming from Taylor that means a lot. This past September, Sports Illustrated profiled Taylor’s career, which began in the late ’70s and ended in the ’80s after a stumble into drugs. Quote after quote from many of the sport’s greats make it clear that Taylor could have been on par with some of the biggest names in boxing. (Basically Taylor is a reformed version of Christian Bale’s character in “The Fighter.”) Charlie trains with Taylor five times a week and maintains an intense fitness regimen. But perhaps most worrisome to Taylor is that Charlie still parties hard. “Means I have to train harder,” Charlie says. “I have to make up for the drinking with extra work. But that’s just who I am.”

One of the people who understands Charlie and Taylor best is the filmmaker Michelle Groskopf. She first noticed Charlie and his crew walking around Park Slope, Brooklyn, seven years ago, when he was 13 years old. After a chance encounter on the subway, she began taking pictures of them, and then shooting film. “Charlie’s coach understands how seductive and distracting the attention and fame can be,” she says. “All eyes are on Charlie now, everyone is expecting something and he knows it. The challenge is to keep Charlie from suffering the fate of Icarus, of burning too brightly and losing sight of the title.” She is currently working on a documentary that explores this relationship.

Charlie and his trainer differ tremendously in their entry point to the sport. For a young black man like Taylor growing up in Brooklyn in the ’70s, boxing could mean an escape from the street, a way to create a future without the opportunity afforded by education. Charlie on the other hand, while not especially wealthy, is solidly middle class and well educated, the son of a prominent tenants’-rights lawyer.

Issues of class and race have always been central to boxing, something apparent even in the underground matches at Throwdown, where often it seems like trained whites are pitted against blacks or Latinos who have more of a street fighting style. “In America, there is a longstanding, complex relationship between the working class and the elite in youth culture,” Groskopf observes. “With the fight club, these identities are exaggerated. In that last fight, Charlie played the gentleman role in contrast to [his friend and opponent] Staxx’s street cred. It riles the audience.”

But she’s careful to point out that with Charlie and Staxx this is something that only exists in the ring. They are entertainers. When the match is over, the two show true camaraderie.

Groskopf was initially drawn to Charlie’s look and style, but she has trouble putting into words how that all fits into the context of pugilism. Is the allure of seeing beautiful guys punch each other out as base as it seems on the surface? One of the few models falling into Throwdown’s effete category is Marcel Castenmiller, who begins to grin at this question. Last October he and another model, Nicholas Hinman, jumped into the ring for a semi-unsanctioned — and very short — bare knuckles (because they couldn’t find the gloves) fight. Skinny as the two are, they really went at it. And despite a solid pummeling to the face, a day or two later Castenmiller posed for a Tommy Hilfiger ad, scratched cornea and all.

“I guess you know you’re not supposed to do it,” he says with a laugh. “So, you just have to do it.”

NYT Style Magazine:

The Gift of Information

Julian Assange, WikiLeaks' mercurial and complicated founder, had the attention of the world. Tracking him down for a portrait and interview wasn’t easy.

-

Julian Assange and WikiLeaks have been jettisoned to fame or notoriety (choose your noun, please) not because of a passing political battle but for reasons much deeper: the desire to possess, distribute and devour information. Ever since the release in July this year of some 92,000 documents relating to America’s involvement in Afghanistan, an old joke from Communist times keeps spinning around my head. ‘‘We cannot predict the future,’’ announces the newsreader of Soviet radio reporting on the Politburo’s deliberations, ‘‘but the past is changing before our very eyes.’’ Now our understanding of the nature of the intervention in Iraq has also changed radically with the publication of a still more astonishing collection of 391,832 secret United States military field reports from the kaleidoscopic theaters of battle.

It has been the eye-opening, game-changing year of WikiLeaks. It started in April, with the release of video shot in 2007 from an Apache helicopter as a group of men on open ground in Baghdad were fired upon. Two of the victims worked for Reuters, as a photographer and driver, and the tragic nature of their deaths was made all the more horrific by the robotic, almost desultory voices of the airmen narrating their actions. The impact was immense. Julian Assange, WikiLeaks’ mercurial and complicated founder, had the attention of the world.

The man suspected of leaking that footage, Bradley Manning, is also thought to be central to the subsequent release of the Afghan and Iraqi documents. His precise motives may never be known, but this much is undoubtedly true: Manning was partly driven by the fundamental human urge to disseminate information, to let others know what he was reading and seeing and thinking from his dusty little military prefab under Iraq’s unforgiving sun. Previously powerless, small but watchful soldiers like Manning and other whistle-blowers discovered in the past half decade a new and efficient vehicle to spread the news: WikiLeaks. The Web site’s reputation grew quickly after its official introduction in 2007. Two years ago, it published a gripping account compiled by the BND, Germany’s foreign intelligence agency, on the links between organized crime groups and political parties in Kosovo. Observers of the former Yugoslavia had known about much of this activity, but the meticulous Teutonic report quickly became an invaluable guide to the grim realities of one of the most unstable areas of Europe.

Assange understands full well the significance of these documents and their surreptitious transmission, and that knowledge translates into power and influence. For most of history, government has enjoyed an easy superiority in adjusting the ebb and flow of information. Now the rules of the contest have changed. In contrast to the petabytes of data flotsam, half-truths and speculation that drift daily around the Internet, WikiLeaks spews forth unvarnished, sensitive truths. Assange’s extraordinary project provides transparency unbridled. Historians, journalists and civic activists will continue to fish in these rich informational waters for some time if the organization does not collapse.

For the world’s militaries it is, of course, a less welcome operation. The Defense Department’s official response to the Afghan documents thundered, ‘‘We deplore WikiLeaks. . . . We know terrorist organizations have been mining the leaked Afghan documents for information to use against us.’’ At the same time, the Pentagon suggested that ‘‘the release of these field reports does not bring new understanding to Iraq’s past.’’ But if they do not bring new understanding to the past, why are they damaging at all? Is this not the curse of power, forever compelled to conceal and dissemble? In his recent memoir, Tony Blair berates himself for introducing a Freedom of Information Act. ‘‘You idiot. You naïve, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop,’’ he writes.

The future, as the Soviet joke reminds us, is impossible to predict. But governments, corporations and individuals are now bracing themselves for battles royal over who controls the gifts of information and narrative. Revelations about the past will continue to bloody the Internet’s pathways. At the same time governments will stuff data back into Pandora’s box, while individuals find new electronic routes for data to reach the public. Assange and his crusaders may be good. Perhaps they are bad. But they have taken everyone’s urge to tell a story to a new and almost wholly unfamiliar level.

A Few Favorite Covers